The meat analogue industry is growing at a rapid pace both in terms of product offering and availability. This has expanded beyond vegetarian consumers where now many meat-eaters are coming on board (1). The types of products on the meat analogue spectrum start at beef-like burgers and chicken-like nuggets, but how many of these meat analogue products are “real”? By “real” we refer to the quality of their ingredients, the levels of nutrition and the transparency of food companies in terms of their marketing practices.

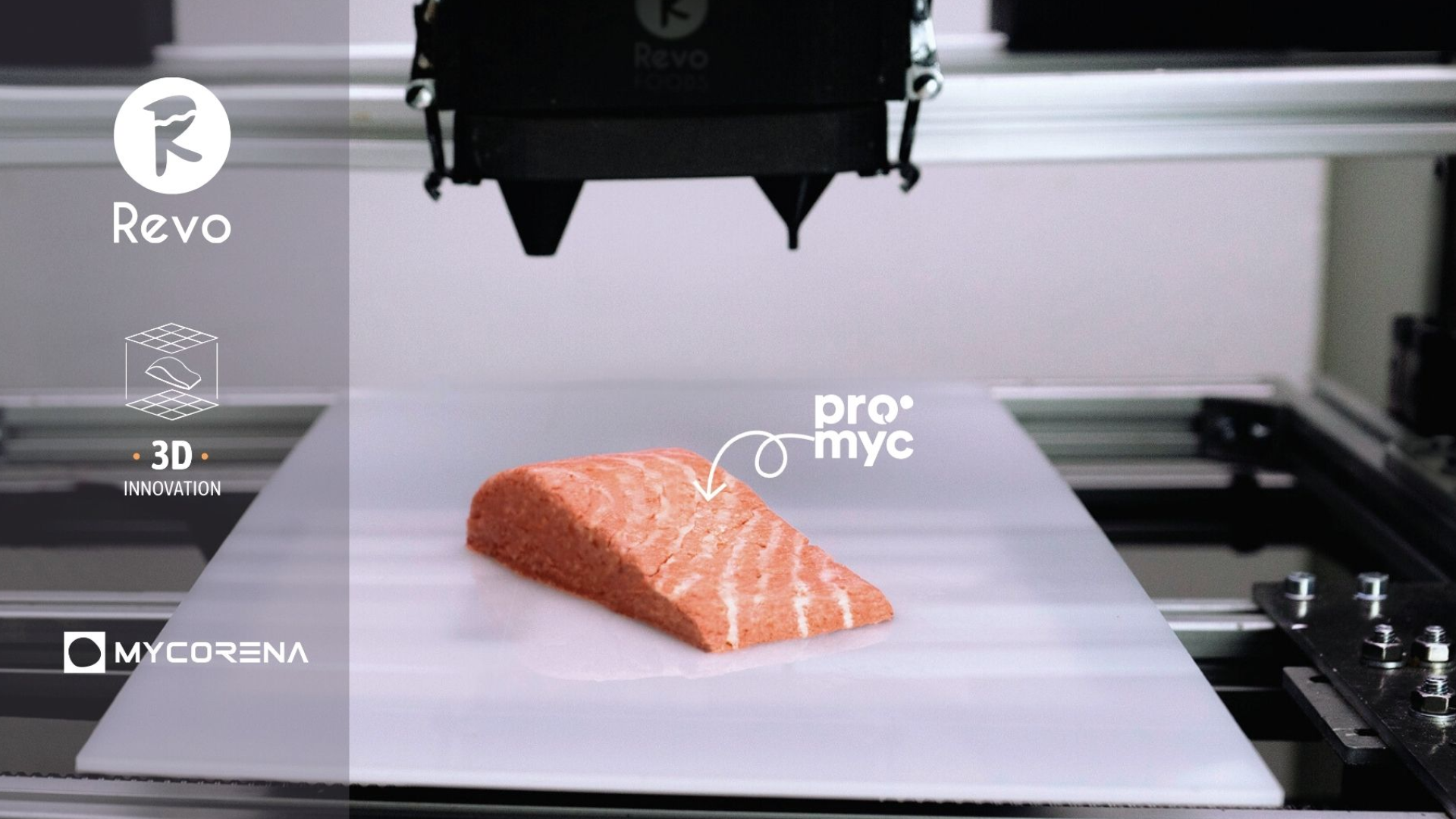

Modern meat analogues are still praised for their ability to meet consumer expectations (2) by ticking the boxes of appearance, texture and flavour. Many plant-based meat alternatives are however highly processed and include unfamiliar ingredients with ingredients lists that are overly complicated. Promyc, our mycoprotein food product, is produced using only a few ingredients i.e. fungi, sugar, nutrients and water in a localised and environmentally sound facility. Compared to that of soybean and pea-based options found in other products on the market, Promyc’s protein content is also significantly higher with the added bonus of essential amino acids.

Ingredients and Nutrition

Animal proteins contain the complete protein package meaning they contain an adequate proportion of each of the nine amino acids fundamental to the human diet along with an acceptable digestibility of these amino acids (2). It is safe to say that meat-eaters looking to expand their horizons into the plant-based meat analogue sector are after a full protein package comparable to animal-based products. Likewise, vegetarian and vegan consumers are looking to obtain the nutrients they need from the food that they consume. In the manufacture of meat analogues, there are several plant-based sources of proteins available but unfortunately not all cover the full spectrum of amino acids necessary for good health nor is their digestibility index at an optimum level.

Protein quality can be, to some degree, quantified by a value called the Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS). Historically, soy proteins have been the most common protein used in meat analogue products where soy protein isolate has a PDCAAS of 0.92 (with 1.00 being the highest possible value) (U.S. FDA – https://www.fda.gov/home). Cereal proteins such as wheat, rice and barley are generally higher in carbohydrate content and when compared to soy, significantly lower in protein content (2). Legume proteins, in particular pea proteins, are rising in popularity despite challenges with digestibility and protein quality with a PDCAAS score between 0.40 to 0.89 depending on the legume product. Mycoproteins, however, have a PDCAAS score of 0.996 (3); higher than the aforementioned soy and legume.

Furthermore, meat analogue products tend to contain carbohydrates in the form of starches or flours for texture and consistency, or binding ingredients such as methylcellulose and gums to enhance the form and stability of the product (2). Both methylcellulose and gums have attracted some criticism of their nutritional effects. Either way, the push from consumers for cleaner labels has influenced food manufacturers to either completely eliminate or limit the usage of these additives in many processed food products. Carbohydrates can be perceived in two ways: they can either be seen as a health-positive addition to one’s diet due to greater dietary fibre and on the flipside – detrimental to one’s health as a result of refined starches and/or sugars (4). Either way, if carbohydrates are purely used as a filler mechanism for meat analogue products, it is highly probable that other nutritional components, such as the amount of quality protein, is amiss.

Another important aspect to consider is the amount of sodium in the meat substitute products found on supermarket shelves currently. Considering how high sodium diets have been shown to increase blood pressure levels leading to a greater risk of heart disease (5), it is surprising that not more has been done to combat the issue. With traditional meat eaters joining non-meat eaters in their quest for healthier protein alternatives, a common oversight when comparing animal versus plant-based alternatives is the amount of sodium (6).A 2018 UK-based study showed that 28% out of the 157 meat substitute products evaluated contain higher levels of salt than the maximum recommendation by the UK government (7).

Marketing Practices

The way in which plant-based meats are labelled is a growing global concern. Lobbying in Australia, the USA and the European Union has put the labelling of plant-based meats in the spotlight. The issue is that the imagery and the use of meat-related words used by food manufacturers today mislead consumers into thinking that the range of nutrients naturally found in meat is equally present in plant-based meat counterparts (8, 9).

This health halo effect works to not only veil the amount of protein but also the number of unnecessary additives. In addition, levels of sodium are generally overlooked. It is important for both food manufacturers to offer food products that are nutritious and healthy whilst it is equally important for governments to introduce food standards and policies to ensure that the playing field is a transparent one.

Conclusion

As consumers become increasingly aware of not only what their food contains but where it comes from, alternative sources of complete protein such as mycoproteins will pave the way for a yellow brick road to a more environmentally sound and healthy future.

Authors:

Tamara Adzic

Business Developer at Mycorena

References

- K. Kyriakopoulou, B. Dekkers, A.J. van der Goot., 2007. Plant-based meat analogues. Sustainable Meat Production and Processing, Academic Press, pp. 103-126, 10.1016/B978-0-12-814874-7.00006-7

- Bohrer, B., 2019. An investigation of the formulation and nutritional composition of modern meat analogue products. Food Science and Human Wellness, Volume 8 Issue 4, pp. 320-329. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213453019301144?via%3Dihub

- https://assets.ctfassets.net/2bynbqpgfb2s/5Vdj3dXA9UowGY8WwSqa4m/47c733f6156cd5c7f3d8ae589f1d6c92/health_benefits_mycoprotein_factsheet.pdf Accessed 28 Sept. 2020

- Topping, D., 2007. Cereal complex carbohydrates and their contribution to human health. J. Cereal Sci., 46, pp. 220-22

- “75% of Americans Want Less Sodium in Processed and Restaurant Foods Infographic.” Www.Heart.Org, www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/sodium/75-of-americans-want-less-sodium-in-processed-and-restaurant-foods. Accessed 28 Sept. 2020.

- CNN, Nina Avramova. “Meat-Free Burgers Contain More Salt than Real Burgers, Survey Shows.” CNN, edition.cnn.com/2018/10/23/health/meat-free-burgers-less-healthy-than-real-meet-intl/index.html. Accessed 28 Sept. 2020.

- “Meat Alternatives Survey 2018 – Action on Salt.” Actiononsalt.Org.Uk, 2018, www.actiononsalt.org.uk/salt-surveys/2018/meat-alternatives-survey/. Accessed 27 Sept. 2020

- Li N., Lloyd O. “Will the Australian Food Regulator Change Its Tuna”?, https://www.allens.com.au/insights-news/insights/2019/08/will-the-australian-food-regulator-change-its-tuna/. Accessed 25 Sept. 2020

- Barbour L. “Nationals Push for Ban on Plant-Based, Alternative Products Being Called ‘Milk’, ‘Meat’,‘Seafood’”,https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-09-15/push-to-ban-milk-meat-seafood-labels-on-plant-based-produce/11513754. Accessed 26 Sept. 2020