So is Mycorena creating mushroom protein? Well, not necessarily mushrooms as you think. Mycorena is using fungi! The type of fungi is called filamentous fungi as it is thread-like in structure and just so happens to not create any fruiting body of mushrooms. Where it can get a bit confusing is when translating to Swedish. In Swedish, both fungi and mushrooms are called “svampar”. But now you know! Mycoprotein is a type of protein that is derived from fungi where “myco” is from the Greek word for “fungus”.

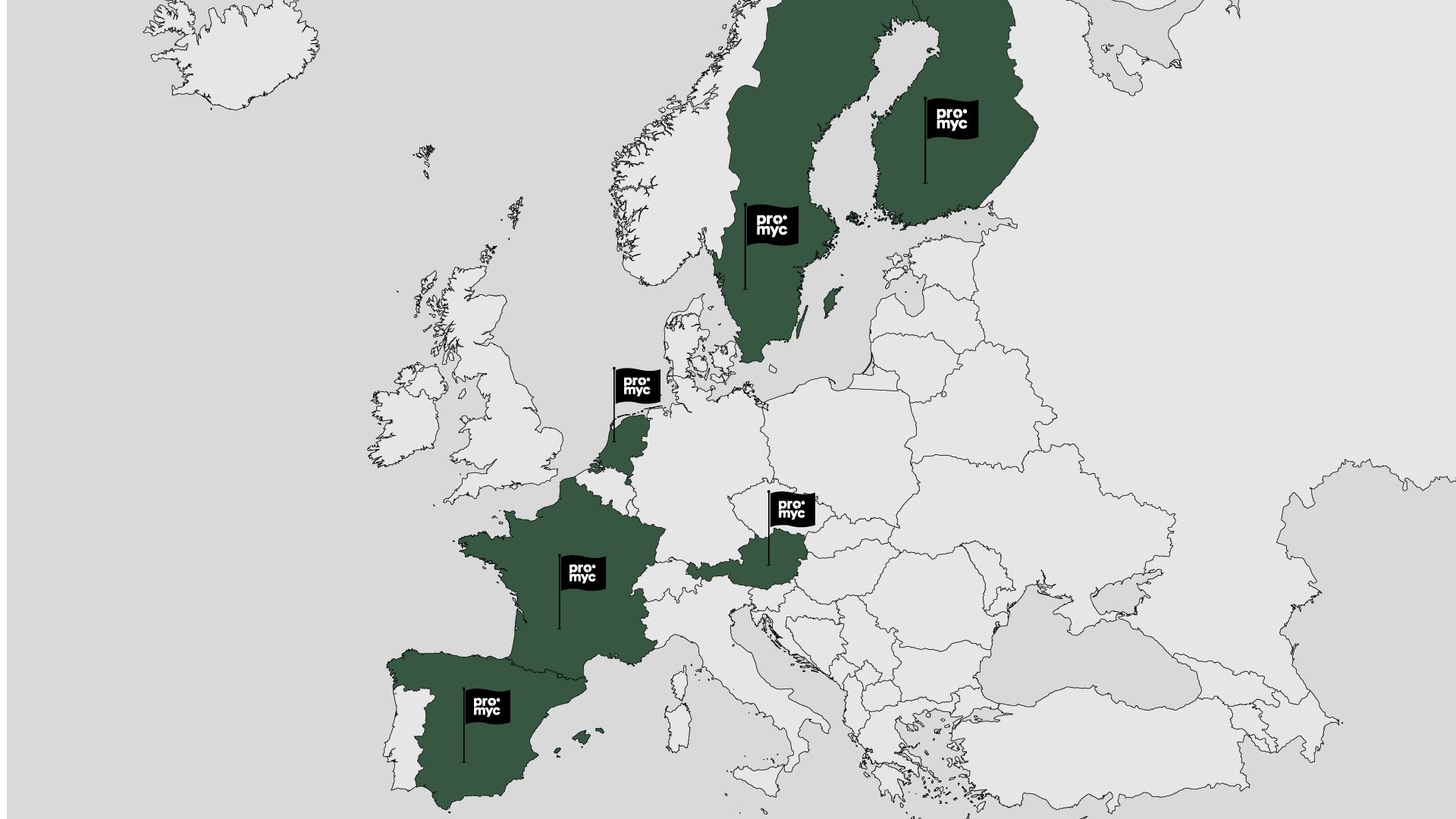

The interest in mycoprotein worldwide is growing (Figure 2) whilst geographical interest for mycoprotein is shown in Figure 1 below. The interest is strongest in the UK and Irish markets which can be explained by the fact that Quorn is an established UK-based company and consumers are aware of their products there. Sweden ranks 7th as the country that searches for “mycoprotein” worldwide.

Mycoprotein is on an increasing interest trend. This confirms the buzz that is happening around what Mycorena is doing and that consumers are in fact getting more interested not only in plant-based foods but also specifically in mycoprotein.

What is interesting, however, is that the majority of search engine questions relating to “mycoprotein” relate to questions about ingredients, how it is made and if there are any side effects. This differs largely from the type of search engine queries that relate to soy protein for instance. These queries relate to questions about whether soy is a plant-based protein, soy based protein powder and the difference between soy protein and pea protein.

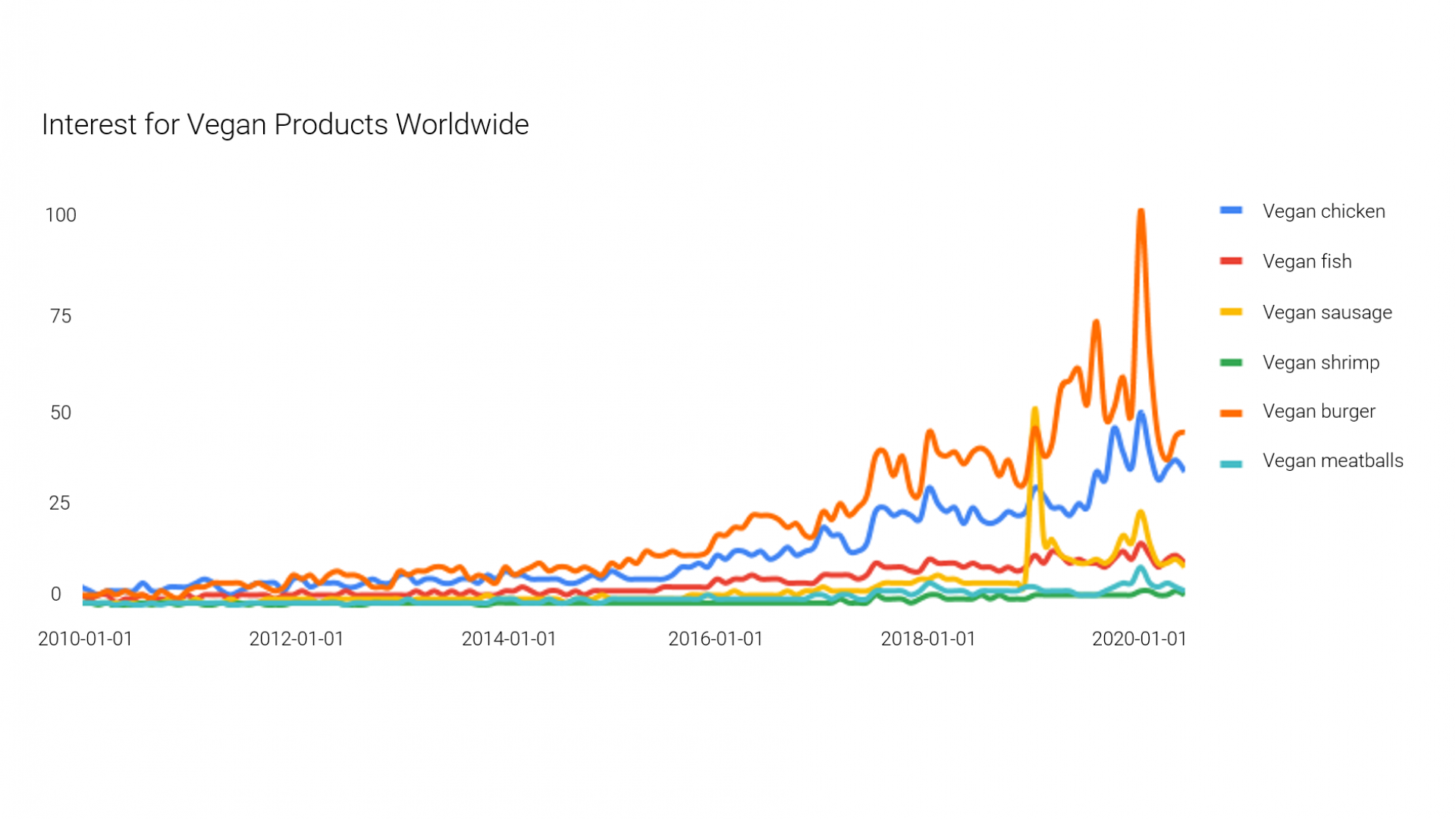

Searches for different vegan products and the trends can be seen in Figure 3 below. Vegan burger is the number one most searched, and vegan chicken is the second most searched for. The high interest can be interpreted in different ways; people are searching for it because they know it exists, or that people are searching for it because they are demanding it. Seeing as vegan fish is at such a low interest does not necessarily mean that the consumer interest for vegan fish is low, however compared to burgers and chicken it can be harder to get the same traffic. This could potentially be due to the fact that burgers and chicken-like products have dominated the consumer goods market and therefore through establishment have been the primary choices. During the 1st of January 2018-2020, there had been a reoccurring spike that people are searching more for all vegan products. This could be explained by people wanting to live healthier and change their habits by eating more vegan products, and also by “Veganuary” becoming a trend during the start of 2020.

Doing searches in Swedish, the interest is seen in Figure 4 below. The spike in interest for “veganska köttbullar” is happening at Christmas time each year. Because who doesn’t want vegan meatballs!? In June 2020, vegansk kyckling, korv, köttbullar and hamburgare has the same relative number of interest, while vegansk fisk has 0 (not zero searches, but in relative terms no interest).

APPENDIX: Google Trends adjusts search data to make comparisons between terms easier. Each data point is divided by the total searches of the geography and time range it represents, to compare relative popularity. Otherwise, places with the most search volume would always be ranked highest. Different regions that show the same search interest for a term don’t always have the same total search volumes. The resulting numbers get scaled on a range of 0 to 100 based on a topics proportion to all searches. This means that 100 is the most interest that has ever been happening during the search period.

Research articles in the field of mycoproteins is also on the incline. Compared to other protein sources such as pea protein and chickpea protein, mycoprotein has flown under the radar in terms of commercial applications. A part of the reason as to why this is so can arguably be put down to the fact that there is limited publicly available knowledge in terms of the technology.

The research that did focus on mycoprotein specifically has produced some interesting insights. Firstly, an article published in 2020 ‘Mycoproteins as safe meat substitutes’ by Hashempour-Baltork et. al (2020) is one of the first of its kind to specifically outline that mycoprotein-based food products are safe consumables. There are, however, three published research papers that were found to paint mycoproteins in food and feed products in a negative light. One such article by Burden, W.L. (2019) ‘Mycotoxins in the Food Chain and Human Health Implications’, suggests that mycotoxins may cause mycotoxicosis resulting in an acute or chronic disease episode when ingested. On the contrary, Mycorena’s unique fungal strain does not produce mycotoxins. Also, compared to soybean and pea, the protein and amino acid content in Mycorena’s Promyc is significantly higher. We are working hard to make sure these messages are received!

Continuing on the consumer knowledge about mycoprotein, it has long been accused of giving consumers allergies. The Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI) has collected reports on both GI (gastrointestinal intolerance) and allergic reactions for almost 20 years (Finnigan et al. 2019). CSPI claims that mycoprotein is unsafe, but they fail to present the denominator that would allow for an estimate of the frequency of unsafe reactions. They indicate that 63% of people who first ate mycoprotein had adverse reactions. With mycoprotein, the body needs to be sensitized first and it is much more likely that the reactions are GI in nature and not allergic reactions (Finnigan et al. 2019). It is also important to highlight that self-reported data, like the dataset for CSPI, has to be treated with caution since it is based on self-diagnoses.

Marlow Foods has collected consumer complaints since 1985 when they entered the UK market. They can be argued to be seen as a very good indicator since they have successfully commercialized mycoprotein for a long time. Finnigan et al. (2019) has analysed the reports for a span of 15 years, and the occurrence of adverse reactions is exceptionally low. The reported illnesses were characterized as GI or true allergy with symptoms beyond GI. Over the 15 years, the reported illnesses was 1 per 683,665 packages or 1 reported illness per 1.85 million servings. Only 42 of the total number of reports suggests that some form of medical treatment was needed, that is 1 in 37.9 million packages sold. The rate of allergic reactions is very low, 1 in 9 million packages.

From an allergy perspective, mycoprotein may be among the safest novel protein sources on the market according to Finnegan et al. (2019), however the authors want to see more research that focuses on long-term clinical benefits of consuming a diet containing mycoprotein. Hashempour-Baltork et al. (2020) mentions that it is only a few studies showing allergic and toxic effects of mycoprotein where previous studies have shown that allergic reactions to mycoprotein are drastically less than for other protein sources such as soy. We at Mycorena hope to see that many new studies are disclosed, showing the benefits from eating a varied diet including mycoprotein. Additionally Mycorena’s mycoprotein product, Promyc, is also saturated fat and sugar free with a low fat content.

It is suggested that the resemblance of meat in terms of taste and consistency are influential aspects of the increasing acceptance of mycoprotein as a substitute for meat. But also, the fact that Mycoprotein offers a great replacement for other chemically derived equivalents (Matassa, 2016). Although search trends and the number of published research articles is on the rise, more needs to be done to ensure that consumers have mycoprotein on their radar when they seek out and purchase protein-based food products. Targeted marketing campaigns with a focus on the naturality of mycoprotein along with packaging that highlights granted labels such as the V-Label as a seal of quality for vegetarian and vegan products, or labelling schemes highlighting the origin of production, will assist in spreading the message about mycoprotein as a sustainable, safe and healthy foodstuff. Still, the acceptance of products derived from mycoprotein faces the challenge of general unfamiliarity among consumers towards the food ingredient. From terms like “mold”, or “fungi”, it is suggested that such descriptions can create negative associations for mycoprotein foodstuffs (Bashi et al., 2019).

With attempts to use a familiar reference point for consumers, terms like “plant-based” have been used to describe the products. However, it is questionable whether such a reference accurately captures the product profile. This exposes the dilemma many companies within the industry are facing, when attempting to provide an appealing but correct description (Fassler, 2019; Danly, 2020). The question is though, with a superior nutritious consistency and texture than equivalent plant-based products, why should products of mycoprotein settle with “only” being described as plant-based? Why not use it as an advantage to differentiate from other plant-based products?

We believe that one of the key issues is that consumers do not know what mycoprotein really is. When consumers see a package of a product containing mycoprotein, what does that really mean? It is important to have available information that shows the naturality of fungi, since it has been used for so many years in many cases, like yeast and soy sauce. Also, Mycorena’s Promyc is produced using only a few ingredients i.e. fungi, sugar, nutrients and water.

Transparency is therefore seen as key, both internally and externally. In fact, in a report from 2018 by Label Insights, it was found that while 93% of consumers considered it as important for brands and food producers to show detailed information of the ingredients and production methods on food products, most respondents found it confusing to understand the actual content after reading the ingredients list. From this perspective, providing consumers with full transparency regarding description of all ingredients, thorough information about the nutrition, and full disclosure of allergens, production methods and ways for sourcing the ingredients are considered as key aspects to ensure the trust and acceptance among consumers (Amway, 2019). Increasing internal communications between the business and technical departments will help facilitate a greater knowledge exchange. This knowledge can then be shared with consumers, ultimately increasing external transparency in the consumer sphere whilst simultaneously encouraging an external knowledge exchange with other actors on the market.

APPENDIX: Google Trends adjusts search data to make comparisons between terms easier. Each data point is divided by the total searches of the geography and time range it represents, to compare relative popularity. Otherwise, places with the most search volume would always be ranked highest. Different regions that show the same search interest for a term don’t always have the same total search volumes. The resulting numbers get scaled on a range of 0 to 100 based on a topics proportion to all searches. This means that 100 is the most interest that has ever been happening during the search period.

Authors:

Tamara Adzic

Marketing Intern at Mycorena

Rasmus Kockgård

Business Intern at Mycorena

Andreas Utberg

Business Intern at Mycorena’╗┐

References

Bryden, W.L. 2019. Mycotoxins: Natural Food Chain Contaminants and Human Health. Encylopedia of Environmental Health, p. 515-523

Finnigan, T., Wall, B., Wilde, P., Stephens, F., Taylor, S. and Freedman, M. 2019. Mycoprotein: The Future of Nutritious Nonmeat Protein, a Symposium Review. Current Developments in Nutrition, 3(6).

Hashempour-Baltork, F., Khosravi-Darani, K., Hosseini, H., Farshi, P. and Reihani, S. 2020. Mycoproteins as safe meat substitutes. Journal of Cleaner Production, 253, p.119958

Matassa, S. et al., 2016. Microbial protein: future sustainable food supply route with low environmental footprint. Microbial Biotechnology, 9(5), pp.568–575.

Amway, 2019. No Secret Ingredients: The Importance Of Food Transparency. Forbes, December 19th. [2020-07-07]https://www.forbes.com/sites/amway/2019/12/19/no-secret-ingredients-the-importance-of-food-transparency/#686fb4aa160b

Bashi et al., 2019. Alternative proteins: The race for market share is on. McKinsey. [2020-07-07] https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Agriculture/Our%20Insights/Alternative%20proteins%20The%20race%20for%20market%20share%20is%20on/Alternative-proteins-The-race-for-market-share-is-on.pdf

Danley, 2020. Is fungi-based protein the future of fake meat? Food Business News. [2020-07-07] https://www.foodbusinessnews.net/articles/15226-is-fungi-based-protein-the-future-of-fake-meat

Fassler, 2019. A startup just announced the world’s first fake-meat “steaks” made from fungi. Are we ready? The Counter. [2020-07-07] https://thecounter.org/move-over-plant-based-meat-fungi-steaks-are-here/